When last we checked in on Pte. George Ramsay Acland Mills, S/440048, of the Army Service Corps, he had just completed work to gain his certificate in shorthand and typing on 18 December 1918, just five weeks after the signatures had dried on the Armistice that ceased hostilities on the Western Front.

George must have had it in his mind to return home to his new address in London. While in the service, his parents and sisters had moved from 38 Onslow Gardens in Kensington to the home of George's maternal grandfather, Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay, at 7 Manson Place, Queen's Gate, S.W. The aging Ramsay was 90 years old at the time, and had served as Director of Clothing at the Army Clothing Depôt, 1863-1893, in whose service he was named to the Civil Division, Third Class, of the Most Honorable Order of the Bath in 1882.

Sir George's wife, Eleanor Juliat Chartris Crawford Ramsay, Pte. George's grandmother, had passed away on 15 March 1918, a death which likely precipitated Sir George's daughter, Edith, and son-in-law, Rev. Barton R. V. Mills, and/or their children moving in with Ramsay.

Am I the only one who finds it remarkable that a completely unsuccessful and unsuitable army clerk like George Mills was given another chance to redeem himself, this time in the Army Service Corps—a corps affiliated with the Army Clothing Depôt, in which Sir George [right] had made a name for himself, in part for having begun the use of a twilled cloth called khaki under his stewardship?

Am I the only one who finds it remarkable that a completely unsuccessful and unsuitable army clerk like George Mills was given another chance to redeem himself, this time in the Army Service Corps—a corps affiliated with the Army Clothing Depôt, in which Sir George [right] had made a name for himself, in part for having begun the use of a twilled cloth called khaki under his stewardship?Ramsay was ninety at the time, yes, but might he still have had some strings to pull down in the war department on behalf of his struggling grandson and namesake? That is, if, indeed, George had let anyone in the the family know of his difficulties!

Either way, we have no reason to believe that George did not begin work as a clerk somewhere in the Army Service Corps almost immediately after the completion of his training. With the Army Pay Corps already having commandeered the lion's share of the able clerks at the time, and with the APC probably then needing even more as soldiers began to demobilise, it's hard to imagine Mills didn't end up sitting in front of a typewriter somewhere, at a desk, typing something for someone.

Demobilization must have involved the Army Service Corps, keeping track of soldiers' issued items. Here's an excerpt from an on-line description of some of those duties written by Terry Reeves at the Great War Forum:

"Men were allowed to keep their uniform, with the exception of those discharged from hospital. Those arriving from overseas with steel helmets were allowed to retain them. Great coats could be kept, but £1-00p was deducted from the man's pay. He was issued with a great coat voucher however. If, within a specified period of time he handed it in at his local railway station, he would be reimbursed on the production of the voucher.

A Dispersal Certificate recorded personal and military information and also the state of his equipment. If he lost any of it after this point, the value would be deducted from his outstanding pay."

Mills may not have been involved in that sort of accounting and paperwork exactly, but when experienced clerks began doing those new tasks, it seems likely that their more routine chores would have fallen to him—the new fellow.

Mills hardly had a chance to warm his chair in the ASC, however, when he was called for demobilization and discharge as well. Reeves continues:

Mills hardly had a chance to warm his chair in the ASC, however, when he was called for demobilization and discharge as well. Reeves continues:"Men were sent to special dispersal units for demobilization. Whilst there, they were issued with all the necessary documentation after which they would be sent on leave. For most men, demobilization automatically took place at the end of the leave period."

Not quite so for one George Ramsay Acland Mills, however. Here's a typed document from his file [left] that is dated 30 January 1919, some six weeks after completion of his own coursework in shorthand and typing, indicating he had finally had been selected for demobilization, but it didn't go through immediately. It reads: "O.C. Clerks Boy. Please note that S/440048 Pte George Mills (group 43) who has been held up can now be spared for demobilization." It is signed by the Lieutenant Colonel in charge of the Reserve Supply Personnel Depot of the Army Service Corps. The location given is "12, Eversfield Place, Hastings."

No reason is given for Mills having been held back prior to 30 January, but this document does seem to release him at that point.

But, wait! Not so fast….

Yet another document, this one a handwritten memorandum [right] penned by Capt. C. Washington of the Royal Army Medical Corps, medical officer in charge, R.A.S.C., at 26 Eversfield Place. It was sent to the "OC. Clerks boy" at "Warrior Square," and it reads: "3 February 1919 S/440048 P/E G.R. Mills. Herewith documents of above named man returned as he is undergoing treatment. Please cause him to report then(?) with documents on completion of treatment."

Yet another document, this one a handwritten memorandum [right] penned by Capt. C. Washington of the Royal Army Medical Corps, medical officer in charge, R.A.S.C., at 26 Eversfield Place. It was sent to the "OC. Clerks boy" at "Warrior Square," and it reads: "3 February 1919 S/440048 P/E G.R. Mills. Herewith documents of above named man returned as he is undergoing treatment. Please cause him to report then(?) with documents on completion of treatment."It was 3 February and Mills was held up yet again! This time it definitely appears to have been for medical reasons.

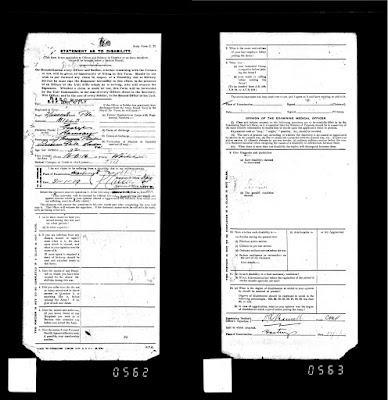

George finally did end up being demobilized, however, a process that seems to have started sometime in advance of 30 January 1919. On George's Army Form Z. 22., STATEMENT AS TO DISABILITY., he claimed he had not been disabled during his time spent serving under the Colours for the duration of the war. It was signed by the commanding officer of the RSPD, ASC, and clearly dated 31 January 1919.

Mills had been sent to make that "statement as to disability" the day after receiving the typewritten card above. Something must not have clicked, however, so scratch that: He was delayed again.

We can see on Army Form Z. 22. [pictured below, left] that Mills was finally given his demobilization physical in Hastings on 17 February 1919 by our old friend, Dr. H. R. Mansell, C.M.P. We can see that on the typewritten card mentioned above someone has scrawled "Action 18 — 2 — 19." George was finally on the move!

What had delayed Mills for well over two weeks, perhaps more than three, during which time he must have been simply itching to return to London and his family?

There is some ghost writing on side one of Army Form Z. 22. [click the form, left, to enlarge it] that can, in fact, be clearly be read on this sheet, not in the cells of the tables that have been left blank unilaterally, but in the marginal areas. To the left, we see the words "under treatment" written in script next to George's particulars (name, rank, serial number, etc.). It's hard to tell if it is written in pencil, or if it is the result of some misplaced carbon paper.

There is some ghost writing on side one of Army Form Z. 22. [click the form, left, to enlarge it] that can, in fact, be clearly be read on this sheet, not in the cells of the tables that have been left blank unilaterally, but in the marginal areas. To the left, we see the words "under treatment" written in script next to George's particulars (name, rank, serial number, etc.). It's hard to tell if it is written in pencil, or if it is the result of some misplaced carbon paper.Above those same particulars, we again see written in a ghostly but clearly readable script—either in pencil or carbon—the words "Dobies Itch."

Dobie's Itch didn't jump right out at me immediately, first because I had no idea what it was. Based on a quick googling, I discovered that's because we in the United States today usually refer to it as "Jock Itch" (or the more vulgar "Crotch Rot"), while UK websites now call the same thing Dobie's Itch. Secondly, it never occurred to me that a soldier could be held up for nigh upon three weeks for that sort of seemingly insignificant treatment. Looking over literature from the era, however, it seems "Dobies Itch" may have been used then as another term for "ringworm."

Frighteningly, regarding Ringworm, Wikipedia states: "Dermatophytosis has been prevalent since before 1906, at which time ringworm was treated with compounds of mercury or sometimes sulfur or iodine. Hairy areas of skin were considered too difficult to treat, so the scalp was treated with x-rays and followed up with antiparasitic medication."

Indeed, on p. 735 of the 12 December 1918 edition of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (vol. 179) an article regarding x-rays, "Ten Years' Experience with Ringworm in Public Elementary Schools," states: "[T]his offers a convenient mode of epilation, which is necessary to get at the mycelium and spores... but the drawback is the time required, about two months; and, besides, there is the temporary baldness, and, theoretically, the fear of damage to the brain cells. It is also a somewhat costly method."

Indeed, on p. 735 of the 12 December 1918 edition of the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal (vol. 179) an article regarding x-rays, "Ten Years' Experience with Ringworm in Public Elementary Schools," states: "[T]his offers a convenient mode of epilation, which is necessary to get at the mycelium and spores... but the drawback is the time required, about two months; and, besides, there is the temporary baldness, and, theoretically, the fear of damage to the brain cells. It is also a somewhat costly method."In the 1918 text Medicine and Surgery, H. H. Hazen, M.D., wrote an chapter entitled "Dermatology and the War." On page 145, he states: "Acne is objectionable chiefly because it is so unsightly I have already published my observations of x-ray treatment of the disease, and further observations have served to show that it is the quickest and surest means of cure, and permanent cure.

Ringworm of the groins has been common in men who have served in Gallipoli and Egypt. The British dermatologists report many such cases among the officers, and it is only fair to assume that the privates have suffered just as frequently."

It's hard to tell if that last sentence was intended to be a pun or not, but we must realize that, while "Dobie's Itch" may have been amusingly vulgar for the men to laugh about (then and today), the treatments 100 years ago were no laughing matter from the perspective of medicine nowadays. (I'm reluctant to use the term "modern medicine," for these horrible treatments were exactly that in 1918.) In fact, we recently read of the above Dr. Mansell's malpractice difficulties regarding his well-meaning use of x-rays simply to diagnose a broken leg!

Here's one last snippet, from a textbook called Diseases of the Skin by Richard Lightburn Sutton, published in 1919—presumably with treatments up to the 1918 standards that would have been applied to George Mills.

Here's one last snippet, from a textbook called Diseases of the Skin by Richard Lightburn Sutton, published in 1919—presumably with treatments up to the 1918 standards that would have been applied to George Mills.The section on treatment of ringworm begins on page 975, and the photographic illustrations are an absolute nightmare—b&w medical illustrations meet Heironymus Bosch [examples are pictured, left, and above, right]. Laboring under the assumption that the modern-day connotation of "Dobie's Itch" (sometimes Dhobi's Itch) as having something to do with the "crotch" might mean that George's treatment, circa 1918, focused in that specific area of his body, this may best describe his treatment. Let’s hope so.

The text reads: "In ringworm of the crotch and axillae [Sutton's emphasis], it is often necessary to apply soothing remedies, as Anderson's antipruritic powder, calamine lotion, and similar preparations first, and antiseptics later. Of the latter, an aqueous solution of sodium hyposulphate (10 to 15 per cent) is one of the best, although carbolized solutions of resorcin (2 to 10 per cent) and mild parasiticidal ointments (ammoniated mercury, suplhur, and salicylic acid) sometimes act well… Even after the disease is apparently eradicated, it is usually advisable to emply a non-irritating parasticide, as an ointment containing ammoniated mercury (2 to 5 per cent) or an aqueous solution of sodium hyposulphide, for a period of several weeks to guard against relapses."

If that wasn't the treatment he received—and that would have been the better choice looking at it from 2011, although why wouldn't they have thought back then that a combination of ammonia and mercury could do a body good?—then my heart goes out to Mills. If he underwent x-ray therapy, something we know was available to Dr. Mansell, it must have been horrific and might easily explain his inability to have children later in life.

Still, repeatedly swabbing ammoniated mercury on any part of his body, particularly this private's privates, couldn't have been particularly healthy or pleasant. While I'm sure his bunk mates snickered aloud at his itchy irritation, the entire affliction and course of treatment must have tormented Mills.

On 19 February 1919, Mills finally was demobilised by the Dispersal Unit at the Crystal Palace on Sydenham Hill (by automobile today about 17 miles south of his grandfather's home in Queen's Gate), perhaps with a parasiticidal ointment secreted on his person. He had been given his Army Form Z. 11. to take with him on his "leave," at the end of which he would become a civilian again.

On 19 February 1919, Mills finally was demobilised by the Dispersal Unit at the Crystal Palace on Sydenham Hill (by automobile today about 17 miles south of his grandfather's home in Queen's Gate), perhaps with a parasiticidal ointment secreted on his person. He had been given his Army Form Z. 11. to take with him on his "leave," at the end of which he would become a civilian again.George was home at last.

Is this story over? Not quite.

There would have to be one last strange episode in this saga of George Mills, Rifleman, Lance Corporal, Fatigue Man, Private, Student, and Clerk, and it would be almost a punch line to a running joke. But we'll look at that paperwork next time…

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment