It's a cool, crisp, clear morning here in Florida's horse country. The coffee is hot and strong, though, and it's time to dig into something I've been putting off for a while now. This, however, is where it "fits."

In our last post, we took a look at the situation in which George Mills found himself while serving the Army Pay Corps. Mills was born with some advantages—his father, Rev. Barton R. V. Mills, M.A. Oxon, had inherited a great deal of money upon the death of George's grandfather—and had received an education, as we've seen at Parkfield School in Haywards Heath and Harrow. The senior Mills served as an assistant chaplain in the Chapel Royal, had helped conduct the services for the late Queen Victoria, was a member at the Athenæum, and was a published author and respected biblical scholar.

The 1911 census has the Mills family living in London in a 20-room abode with seven servants and a governess for George's sister, Violet, at their 12 Cranleigh Gardens, S.W., home during the count. Rev. Mills, listed as a "Clergyman, Church of England," had sent his son, George, to Harrow at the time. George attended Harrow from 1910 – 1912, and lived for at least some of his time there in an arts & drama-oriented house called The Grove.

His breeding must have made Mills a polite, fairly intelligent boy, as evidenced by his proclivity for writing later in life, and he must have been a keen observer of people. None of those skills would have proven particularly useful when he landed in the Rifle Brigade, though, in 1916.

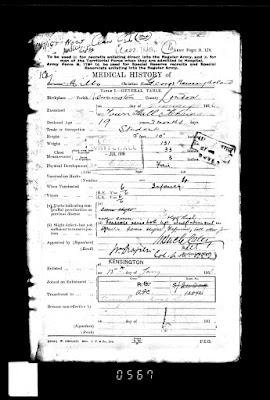

What was Mills like physically at the time? Would he have some advantage in that regard? Fortunately, we have Army Form B. 178., George's MEDICAL HISTORY, to examine.

Mills was examined at the Town Hall in Kensington in January of 1916. He stood 5 feet 10 inches tall—above average for the time—and weighed 131 lbs. His chest, as we've seen on another document, was 30 inches at rest and 33 when expanded, making him somewhat slight.

His "Physical Development" is described as merely "fair."

The record notes he'd been vaccinated in his infancy and had four resulting marks on his left arm.

His vision in each eye was a perfect 6/6. [Is it possible this was the reason he was originally assigned to the Rifle Brigade, which had been originally formed to provide sharpshooters?]

Now, this is where the form gets interesting. It is signed by two gentlemen, and if I am reading the signatures correctly, they were probably Drs. Waley and Draper. Well, presumably they were physicians. The handwriting of both is attendant in section "(b), Slight defects, but not enough to cause rejection."

It appears Draper examined Mills first and recorded the examination particulars mentioned above as well as the following in section (b): "Varicose veins both lips. Impediment in speech."

It appears Draper examined Mills first and recorded the examination particulars mentioned above as well as the following in section (b): "Varicose veins both lips. Impediment in speech."Mills then seems to have been passed on to Waley, who amended Draper's observations about George's varicose veins with "rather severe" and adding "left thigh." He also observed, "Some slight deformity both elbow joints."

Varicose veins, at the time at least, seemingly were not uncommon among military recruits. While statistics from the British army of the era are not readily available on-line, the book Army Anthropology: Based on Observations Made on Draft Recruits 1917-1918, released by the United States Surgeon-General's Office, recorded data from millions of WWI recruits.

The average American recruit (among the first million taken at the time) stood 5' 7 ½" tall and weighed approximately 141 ½ pounds. Their study of varicose veins sufferers among those recruits concluded that the affliction was most likely to occur in northern Europeans. They also note: "It appears at once that the population with varicose veins is characterized by great stature. There is a marked deficiency of men below modal stature and a marked excess of men above… enforcing the conclusion that men with varicose veins are those afflicted primarily because of their tall stature."

Mills, at 5' 10", would have been of "tall stature," at least in the American army. What is odd is that Mills, standing in the 1957 Devonshire Park group croquet photograph, does not appear to be unusually tall among the men on that upper riser. In fact, he appears to be of average size, at least among many of the era's croquet-playing British males.

The report also concludes that varicose veins are more common among men with greater girth, something that was clearly not the case with the slightly built Mills.

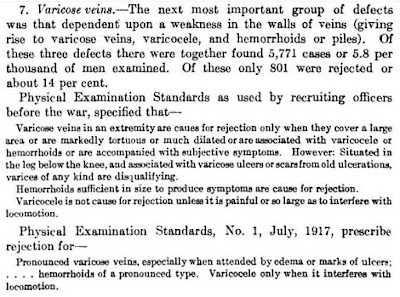

A 1919 Bulletin (Issue 11) from the U.S. Surgeon-General's Office describes recruitment guidelines regarding varicose veins at the time of George's enlistment in this way:

We can't see George's thigh, circa 1916, but I suppose we can assume, since it wasn't his lower leg that was affected, there also must not have been evidence of edema or ulceration for, despite the 'severity' of his varices, he was accepted.

Regarding George's lips, it seems that the varicose veins there must have been either hemangiomas or venous lakes. Neither of these contemporary terms seems particularly suitable: We see no evidence of hemangiomas in that same Devonshire Park photograph in which George, completely clean shaven, seems entirely unafflicted.

In fact 80-90% of all hemangiomas are resolved by natural involution by the age of nine, and most are found on female babies. Mills, however, was over 19 years of age and distinctly male when his were observed and recorded.

Venous lakes, then, may seem more likely as they occur in males in 95% of all cases, and have only been reported in adults. However, they are most common among men over 50 years of age. The average age of presentation of venous lakes is 65. The term "venous lake" is a relatively new one, though, having been first described as such in 1956. That means, for our purposes here, we'll have to look back in time a bit!

In a 1918 medical text, Surgery and Diseases of the Mouth and Jaws: A Practical Treatise on the Surgery and Diseases of the Mouth and Allied Structures, by Dr. Vilray Papin Blair, the author describes "venous and capillary angiomata."

In a 1918 medical text, Surgery and Diseases of the Mouth and Jaws: A Practical Treatise on the Surgery and Diseases of the Mouth and Allied Structures, by Dr. Vilray Papin Blair, the author describes "venous and capillary angiomata."In a section on page 539 called "Tumors of the Blood Vessels," the author writes: "Capillary nevi [lesions], similar to those seen on the skin, composed of a mass of dilated capillaries, occur on the tongue, cheeks, and lips… [Upon] the lip they may be continuous with a wine spot [hemangioma] upon the face. They are of a bluish color, darker than their surroundings, and at the periphery an interlacing of small vessels is visible. They may be single or multiple or may converge into the venous cavernous form of angioma."

Dr. Blair writes of those angiomata: "Parts of the lips, cheeks, and floor of the mouth and face may be converted into a soft, compressible tumor of a bluish color on its mucous surface and slightly more reddish on the external."

His suggestion for treatment: "As a general proposition, all angiomata should be destroyed or removed." I'll pass over some graphically disturbing methods of destroying some angiomata and continue as he relates: "[There] are three lines of treatment that may come within the domain of good surgical practice: (A) the ligation of vessels; (B) the destruction of the mass by acupuncture; and (C) the excision of the mass, either by dissecting it out or by cutting through the surrounding healthy tissue."

After much more graphic description of ligatures and excision, the author concludes his discussion with the sentence: "Small, and even large, nevi have been destroyed by the electric needle."

Are these angiomata what actually afflicted George's mouth? It certainly may have been the more specific diagnosis at the time, but we'll probably never know. It does seem extremely likely, however, that George Mills must have undergone treatment for those "varicose veins" upon his lips after the war, probably before his lavish wedding in 1925.

Regarding the "slight deformity" of his elbow joints, apparently the most common deformity would be either cubitus valgus [a turning in at the elbow of the 'carrying angle' of the arms] or cubitus varus [the opposite condition, turning out].

In a 1916 text from the Harvard Medical Library, Surgery: Its Principles and Practice, edited by William Williams Keen, M.D., the two deformities above are described thusly:

One cannot know if Mills was afflicted with either condition of the elbows, and whether it may have been the result of an injury or by possibly having contracted "rickets." Still, it was presumably so slight that it wasn't noted by the first examining physician.

Lastly, we find Mills had an "impediment in speech." That's of some contemporary interest as the film, The King's Speech, recently made away with a treasure trove of Academy Awards for its depiction of George VI's struggle with his speech impediment.

In an article in the Quarterly Journal of Public Speaking, vol. 3, 1917, "Correction of Speech defects in a Public School System" by Pauline B. Camp describes studies of 89,077 St. Louis, Missouri, school children and 4,862 Madison, Wisconsin, pupils discovered rates of speech impediments at 2.7% and 5.69% of those populations, respectively. The discrepancy was caused by the fact that the St. Louis study was done via written questionnaire, making the Wisconsin results apparently more reliable.

The impediment categories suggested in the studies were stutters, lispers, and those with 'miscellaneous defects.'

The author relates: "A child with a speech defect is not only held back in school because of his inability to express himself, but is also poorly adjusted to social and economic conditions when he is through with school." This was apparently true in the United States at the time, and while I am uncertain it was the same in Great Britain, I suspect it might have been. Please let me know.

The author quotes a Dr. Wile, then a member of the New York City Board of Education, as saying: "The more pronounced the effect, the more limited the field of activity… The importance of discouragement, anxiety, family distress, embarrassment, diffidence, and shyness upon the development of high moral character cannot be estimated."

Dr. Wiles goes on to discuss how "moral degeneration" is linked to speech pathology, and the author quotes Dr. James Sonnett Green of the National Teacher's Association: "'Living at the tips of one's nerves' through an impediment of speech tends to develop vicious circles of instability, resulting in an increase in criminals, prostitutes, and general failures."

Clearly, Mills was not a criminal or a prostitute, but this was apparently a relatively prevalent view at the time, at least in the United States. And it isn't a stretch to think that George would have been considered a "failure" during his tenure in the army during the First World War, especially as he was sent packing by the Army Pay Corps. It is extremely easy to visualize how "discouragement, anxiety, family distress, embarrassment, diffidence, and shyness" could combine in a young George to produce a soldier with little ability to make an impact while serving in uniform.

Clearly, Mills was not a criminal or a prostitute, but this was apparently a relatively prevalent view at the time, at least in the United States. And it isn't a stretch to think that George would have been considered a "failure" during his tenure in the army during the First World War, especially as he was sent packing by the Army Pay Corps. It is extremely easy to visualize how "discouragement, anxiety, family distress, embarrassment, diffidence, and shyness" could combine in a young George to produce a soldier with little ability to make an impact while serving in uniform.Add in the fact that his half-brother, Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, had attended Sandhurst and was a decorated war hero, having been wounded as a platoon commander in France and Belgium during 1914. Arthur convalesced while writing at first newspaper and magazine articles about his war experiences, and then two popular books, With My Regiment: From the Aisne to La Bassée [Lippincott: Philadelphia, 1916] and Hospital Days [T. Fisher Unwin: London, 1916], seen right. In 1916, Arthiur also married the Lady Dorothy Walpole, daughter of the Earl of Orford before returning to continue serving the Colours in Palestine and China.

When it came to sibling rivalry, young George was simply unprepared to compete, especially in the armed forces. That certainly must have weighed on him.

We now know the adolescent George Mills who showed up at the Town hall in Kensington for his physical was tall in stature, but slight of build, with slightly deformed elbows, varicose veins on his covered thigh and his very much exposed lips, and with an unidentified speech impediment that very likely gave him tendencies to be shy, anxious, and easily discouraged.

A glance at the literature regarding the era's treatment of speech impediments ranges from letting a child outgrow the condition all the way to hypnosis. George and his family, much like the Royal Family in The King's Speech, must have been overwhelmed in trying to determine what, exactly, was the best course of treatment.

A note at the very top of Army Form B 178 reads: "Now Class C.I (One)," and is signed by a Lt. Ellis and dated 11 July 1916, some six months after George's initial examination. There is also a ghost of a Roman numeral 3 (III) beneath that inscription, as if it had been incompletely erased. Was this a prior classification as BIII? There is also a lighter script nearby, though in ink, that also seems to read: "Class. IV.a." followed by the circled word "No."

A note at the very top of Army Form B 178 reads: "Now Class C.I (One)," and is signed by a Lt. Ellis and dated 11 July 1916, some six months after George's initial examination. There is also a ghost of a Roman numeral 3 (III) beneath that inscription, as if it had been incompletely erased. Was this a prior classification as BIII? There is also a lighter script nearby, though in ink, that also seems to read: "Class. IV.a." followed by the circled word "No."Whatever, Mills ended up being accepted into the service, classified as BIII, and assigned to the presumably combat-oriented Rifle Brigade, although there seems to have been some negotiating and/or revision before that was determined.

We now know more about George Mills and his physical condition as he entered the military, although, for example, exactly what affliction impeded his speech remains a mystery—unlike George VI's [dramatized, right]—at least until we can find someone who conversed with him.

We now know more about George Mills and his physical condition as he entered the military, although, for example, exactly what affliction impeded his speech remains a mystery—unlike George VI's [dramatized, right]—at least until we can find someone who conversed with him.We can also now surmise a great deal more about George and how he must have dealt with his military life from 1916 - 1919. It wouldn't be a leap to say that his experience must have left some metaphorical scars on him. We also don't know how much of all of it he shared with his family and how much he internalized in a stiff-upper-lip fashion, the latter of which may have psychologically made things worse.

The combination of his physical condition and his military experience had to color the rest of his life, and in some interesting ways. We'll speculate about that another time—this certainly has been a lot to absorb during one sitting!

More immediately, we recently left Mills as he was permananetly and compulsorily transferred out of the Army Pay Corps in September 1918. For any sort of happy ending to occur for George in terms of the military, he would need training—the acquisition of actual, useful skills.

We'll soon look at what those skills were. Stay tuned…

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)

Correction: Not "lips" but "legs"

ReplyDeleteHence correct sentence is: Varicose veins both legs & left thigh.