Lately we've been dwelling quite a bit on the passing of George Ramsay Acland Mills and members of his family. That subject may be a bit gloomy, a stark contrast to the blazingly sunny and crisp days we've been having here in Ocala, but it's been enlightening as well. Many of our speculations have been affirmed, and when some haven't, the lens seems to have brought them into somewhat better focus.

For example, we've wondered aloud about George Mills and his proclivity to pass from job to job as a schoolmaster from the late 1920s seemingly through the late 1930s. Most of that time was peppered with the fallout of the General Strike of 1926 and the worldwide Great Depression.

The question seemed to be: Did Mills pass from opening to opening, all around the U.K. and even as far afield as Glion, Switzerland, because he simply needed to teach and followed the jobs, or was it because he and his bride, Vera, needed the income.

We know that in 1911, George's family lived at 12 Cranleigh Gardens, SW, while George attended Harrow, and that the census form shows the family having seven servants and a governess attending George's father, Revd. Barton R. V. Mills, his mother Edith, and his sisters, Agnes and Violet. They lived in a home with more than 20 rooms, and were sending a son to boarding school.

It's safe to say the family was not financially distressed at the time.

Later, the family moved in with Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay, retired Director of Army Clothing, and father of Edith Mills. It's unclear what became of the Cranleigh Gardens address (Was it sold or rented? Had the Mills family actually owned it?). Sir George passed away in 1920, while George was away attending Christ Church, Oxford.

Later, the family moved in with Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay, retired Director of Army Clothing, and father of Edith Mills. It's unclear what became of the Cranleigh Gardens address (Was it sold or rented? Had the Mills family actually owned it?). Sir George passed away in 1920, while George was away attending Christ Church, Oxford.

Edith Mills had no living siblings at the time of Sir George's death, and Ramsay's wife had predeceased him. It seems the Mills family then lived for a time at nearby 24 Hans-road, Chelsea, following their departure from Sir George's home at 7 Manson Place, and it is while living there that Barton Mills passed away suddenly on 21 January 1932.

What occasioned the family moves? And how did the career movements of son George Mills (and wife) factor in? It sounds as if the family may have been living in homes large enough to have accommodated George and Vera between his stints as a schoolmaster during the years from 1926 and 1932. It also appears that this was a family accustomed to having servants.

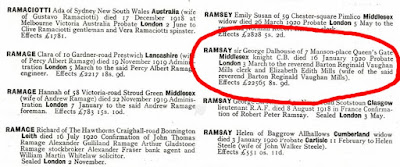

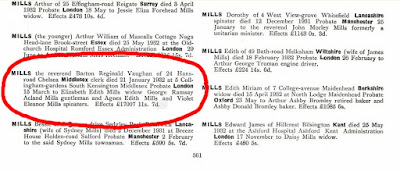

Let's check the probate records. When Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay passed away in 1920, his effects were valued at £22565 8s. 9d., according to figures pulled from records available to ancestry.com [above, left; double-click to enlarge].

To calculate the value of that in terms of today, I went to measuringworth.com and used their indicators. They suggest that when valuing the worth of a person, one should calculate his or her value as a share of the GDP. Their calculations peg the worth of Sir George's estate at a whopping £5,270,000 in 2011 terms.

That's quite an inheritance for Revd. Barton and family!

Let's not forget that Mills departed a stable living as vicar of Bude Haven, Cornwall, to come to London in 1901, after the death of his father, widower Arthur Mills, M.P., also of Bude. Arthur's estate had been probated at £42 305 in 1898. Using the measuringworth.com calculator, that estate was worth £34,400,000, and would have been split among Barton, Barton's brother Dudley, and kin on the Acland side of the family. Even coming away with just 30% of the value of his father's estate, Barton would have left for London knowing he'd secured an inheritance valued at £10,000,000 in 2011.

Is there any wonder there were so many servants?

Is there any wonder there were so many servants?

That examines two inheritances in which Barton had a stake: His father's and his father-in-law's. But Barton himself passed away in 1932. What did he leave behind in terms of wealth?

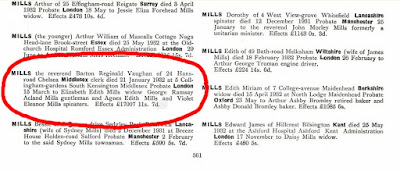

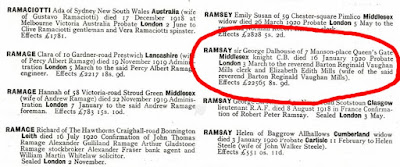

Barton's effects were probated at £17007 11s. 7d. [right]. Admittedly during a worldwide depression, that works out to a mere £5,620,000 in terms of 2011 value.

Barton's estate was bequeathed to Elizabeth Edith Mills, widow, Agnes Edith Mills and Violet Eleanor Mills, spinsters, and George Ramsay Acland Mills, gentleman.

One assumes that real estate values, for example, returned more to normal and continued to accrue value as time went by following the depression. The value of anything invested as such would have grown in value after Barton's passing, making that quite an inheritance.

Looking at those 1932 assets in terms of liquid value, one would use the on-line calculator to compare Barton's "effects" versus the RPI, making it worth "only" £875,000 of purchasing power—a tidy sum today, let alone during the Great Depression!

My hunch is that, unless George had been estranged from his father and/or family during the years between 1925 and 1932, he would likely have been able to avail himself of his family's good will as he bounced form position to position in various preparatory schools and tinkered with authoring his first novel.

It appears that George must have, indeed, wanted badly to teach, and kept at it with the support—presumably often financial—of his family.

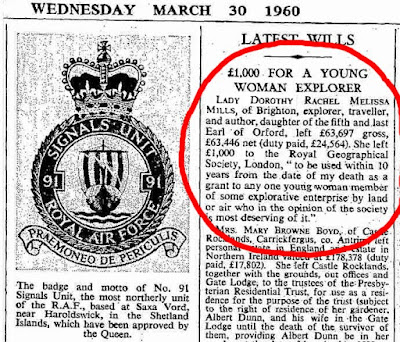

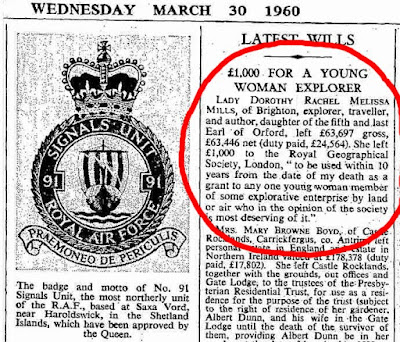

Just for fun, let's also look at the will of Lady Dorothy Mills, once George's sister-in-law, as described in the 30 March 1960 edition of The Times [below, left]. Lady Dorothy was, indeed, estranged from her family, and for lack of other evidence was poor at the outset of her 1916 marriage to George's stepbrother, Captain Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, of the D.C.L.I. To believe that, one must assume that Arthur was also at least somewhat estranged from his family at the time (and, strangely, we have no real reason to believe that), and that the crown was literally paying officers in the infantry a pauper's wage during the First World War (and I'm at a loss to explain why that ever would have made a military career in the UK even remotely attractive).

Anyway, after a lifetime of apparently squeezing her shillings so tightly that King George must have wept, her probate in 1960 netted out at £63446—a value in terms of 2011 totaling £1,090,000.

Anyway, after a lifetime of apparently squeezing her shillings so tightly that King George must have wept, her probate in 1960 netted out at £63446—a value in terms of 2011 totaling £1,090,000.

Passing with over a cool million of 2011 pounds, while living in a seaside hotel with flats in 1958 starting at as little as 9 guineas a week in the winter, it seems that Lady Dorothy had, indeed, come along way from her destitute days of depression, allegedly working in the East End of London, while her family enjoyed their peerage.

Incidentally, the £1000 she bequeathed to the Royal Geographic Society in 1960 that would become the one-time Lady Dorothy Mills Award would be valued today at £17,200.

That certainly leaves a lot for an executor direct to someone or something else.

Lady Dorothy passed away childless, and as far as we know, never remarried after her divorce in 1933.

George, Agnes, and Violet Mills, who would have shared an inheritance from their mother, Edith, when she passed away in 1945, also died unmarried and childless at Grey Friars in Budleigh Salterton. All were no longer with us by July 1975.

Their branch of the family tree came to an end, making the unearthing of the history of their nuclear family so difficult. But one finds it hard to believe that among George, Agnes, Violet, and Lady Dorothy, none had a will, or that they all were inclined to leave the entirety of their estates, and even their personal effects, to the crown.

Ancestry.com has no information on UK wills and probates available after 1940. If we could find out who the executors were of the wills of the Mills, we could have access to persons who potentially would also know details of the Mills family's history—details that could make them and their story all so much more real—including possible access to family photos, letters, passports, post cards, ticket stubs, train schedules, awards, military records, etc. And all of that ephemera could possibly include George's original outlines, character studies, blue-penciled manuscripts for his published books, and perhaps even plans for future texts he'd never gotten around to authoring!

As always, if you can help, please don't hesitate to let me know!

For example, we've wondered aloud about George Mills and his proclivity to pass from job to job as a schoolmaster from the late 1920s seemingly through the late 1930s. Most of that time was peppered with the fallout of the General Strike of 1926 and the worldwide Great Depression.

The question seemed to be: Did Mills pass from opening to opening, all around the U.K. and even as far afield as Glion, Switzerland, because he simply needed to teach and followed the jobs, or was it because he and his bride, Vera, needed the income.

We know that in 1911, George's family lived at 12 Cranleigh Gardens, SW, while George attended Harrow, and that the census form shows the family having seven servants and a governess attending George's father, Revd. Barton R. V. Mills, his mother Edith, and his sisters, Agnes and Violet. They lived in a home with more than 20 rooms, and were sending a son to boarding school.

It's safe to say the family was not financially distressed at the time.

Later, the family moved in with Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay, retired Director of Army Clothing, and father of Edith Mills. It's unclear what became of the Cranleigh Gardens address (Was it sold or rented? Had the Mills family actually owned it?). Sir George passed away in 1920, while George was away attending Christ Church, Oxford.

Later, the family moved in with Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay, retired Director of Army Clothing, and father of Edith Mills. It's unclear what became of the Cranleigh Gardens address (Was it sold or rented? Had the Mills family actually owned it?). Sir George passed away in 1920, while George was away attending Christ Church, Oxford.Edith Mills had no living siblings at the time of Sir George's death, and Ramsay's wife had predeceased him. It seems the Mills family then lived for a time at nearby 24 Hans-road, Chelsea, following their departure from Sir George's home at 7 Manson Place, and it is while living there that Barton Mills passed away suddenly on 21 January 1932.

What occasioned the family moves? And how did the career movements of son George Mills (and wife) factor in? It sounds as if the family may have been living in homes large enough to have accommodated George and Vera between his stints as a schoolmaster during the years from 1926 and 1932. It also appears that this was a family accustomed to having servants.

Let's check the probate records. When Sir George Dalhousie Ramsay passed away in 1920, his effects were valued at £22565 8s. 9d., according to figures pulled from records available to ancestry.com [above, left; double-click to enlarge].

To calculate the value of that in terms of today, I went to measuringworth.com and used their indicators. They suggest that when valuing the worth of a person, one should calculate his or her value as a share of the GDP. Their calculations peg the worth of Sir George's estate at a whopping £5,270,000 in 2011 terms.

That's quite an inheritance for Revd. Barton and family!

Let's not forget that Mills departed a stable living as vicar of Bude Haven, Cornwall, to come to London in 1901, after the death of his father, widower Arthur Mills, M.P., also of Bude. Arthur's estate had been probated at £42 305 in 1898. Using the measuringworth.com calculator, that estate was worth £34,400,000, and would have been split among Barton, Barton's brother Dudley, and kin on the Acland side of the family. Even coming away with just 30% of the value of his father's estate, Barton would have left for London knowing he'd secured an inheritance valued at £10,000,000 in 2011.

Is there any wonder there were so many servants?

Is there any wonder there were so many servants?That examines two inheritances in which Barton had a stake: His father's and his father-in-law's. But Barton himself passed away in 1932. What did he leave behind in terms of wealth?

Barton's effects were probated at £17007 11s. 7d. [right]. Admittedly during a worldwide depression, that works out to a mere £5,620,000 in terms of 2011 value.

Barton's estate was bequeathed to Elizabeth Edith Mills, widow, Agnes Edith Mills and Violet Eleanor Mills, spinsters, and George Ramsay Acland Mills, gentleman.

One assumes that real estate values, for example, returned more to normal and continued to accrue value as time went by following the depression. The value of anything invested as such would have grown in value after Barton's passing, making that quite an inheritance.

Looking at those 1932 assets in terms of liquid value, one would use the on-line calculator to compare Barton's "effects" versus the RPI, making it worth "only" £875,000 of purchasing power—a tidy sum today, let alone during the Great Depression!

My hunch is that, unless George had been estranged from his father and/or family during the years between 1925 and 1932, he would likely have been able to avail himself of his family's good will as he bounced form position to position in various preparatory schools and tinkered with authoring his first novel.

It appears that George must have, indeed, wanted badly to teach, and kept at it with the support—presumably often financial—of his family.

Just for fun, let's also look at the will of Lady Dorothy Mills, once George's sister-in-law, as described in the 30 March 1960 edition of The Times [below, left]. Lady Dorothy was, indeed, estranged from her family, and for lack of other evidence was poor at the outset of her 1916 marriage to George's stepbrother, Captain Arthur Frederick Hobart Mills, of the D.C.L.I. To believe that, one must assume that Arthur was also at least somewhat estranged from his family at the time (and, strangely, we have no real reason to believe that), and that the crown was literally paying officers in the infantry a pauper's wage during the First World War (and I'm at a loss to explain why that ever would have made a military career in the UK even remotely attractive).

Anyway, after a lifetime of apparently squeezing her shillings so tightly that King George must have wept, her probate in 1960 netted out at £63446—a value in terms of 2011 totaling £1,090,000.

Anyway, after a lifetime of apparently squeezing her shillings so tightly that King George must have wept, her probate in 1960 netted out at £63446—a value in terms of 2011 totaling £1,090,000.Passing with over a cool million of 2011 pounds, while living in a seaside hotel with flats in 1958 starting at as little as 9 guineas a week in the winter, it seems that Lady Dorothy had, indeed, come along way from her destitute days of depression, allegedly working in the East End of London, while her family enjoyed their peerage.

Incidentally, the £1000 she bequeathed to the Royal Geographic Society in 1960 that would become the one-time Lady Dorothy Mills Award would be valued today at £17,200.

That certainly leaves a lot for an executor direct to someone or something else.

Lady Dorothy passed away childless, and as far as we know, never remarried after her divorce in 1933.

George, Agnes, and Violet Mills, who would have shared an inheritance from their mother, Edith, when she passed away in 1945, also died unmarried and childless at Grey Friars in Budleigh Salterton. All were no longer with us by July 1975.

Their branch of the family tree came to an end, making the unearthing of the history of their nuclear family so difficult. But one finds it hard to believe that among George, Agnes, Violet, and Lady Dorothy, none had a will, or that they all were inclined to leave the entirety of their estates, and even their personal effects, to the crown.

Ancestry.com has no information on UK wills and probates available after 1940. If we could find out who the executors were of the wills of the Mills, we could have access to persons who potentially would also know details of the Mills family's history—details that could make them and their story all so much more real—including possible access to family photos, letters, passports, post cards, ticket stubs, train schedules, awards, military records, etc. And all of that ephemera could possibly include George's original outlines, character studies, blue-penciled manuscripts for his published books, and perhaps even plans for future texts he'd never gotten around to authoring!

As always, if you can help, please don't hesitate to let me know!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment