I found this, the fourth and last installment of the second trial pitting Miss Valerie Wiedemann against the Hon. Robert Horace Walpole, by far the most surprising—looking at it from the vantage point of the United States in 2010.

Justice may, indeed, be blind, but Justice Mathews certainly was not. After the counsel for the defence, Sir Edward George Clarke, made his closing remarks for the defence in a succinct and gentlemanly way [presumably to avoid seeming like an angry legalistic mercenary of a paternalistic society coming down hard on poor, wronged Valerie], Mr. Justice Mathews—whose duty here would seemingly to have been merely to explain the points of law involved—broke out a metaphorical sledgehammer and pounded his personal suppositions, feelings, and prejudices home into the jury.

Behavior like that today would have been the most shocking aspect of a trial of that nature. Perhaps the lawyers might have indulged, but I feel certain that judges now would have to keep at least some sort of veneer of impartiality in place during proceedings such as these.

Using words like "incredible," "inveigled," "concocted," and "persecuted," contrasting Miss Wiedemann with a "modest woman," pointing out her alleged divergence from the norms of "human nature," and asserting that the gentleman providing critical evidence on behalf of the plaintiff, Uriah Cook, was "untrustworthy" and a "perjured villain," Mathews hammered his opinions home. He even took a verbal swipe at the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, W. J. Stead, and all of the readers of that paper.

Using words like "incredible," "inveigled," "concocted," and "persecuted," contrasting Miss Wiedemann with a "modest woman," pointing out her alleged divergence from the norms of "human nature," and asserting that the gentleman providing critical evidence on behalf of the plaintiff, Uriah Cook, was "untrustworthy" and a "perjured villain," Mathews hammered his opinions home. He even took a verbal swipe at the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, W. J. Stead, and all of the readers of that paper.Mathews even took issue with "the way in which she denied" an allegation by the defence, directed the expectations of the jury, saying "One would have expected," in regard to Wiedemann's actions, and even pointed out the telling fact that, given a note for £100, that check had been very suspiciously "cashed at once" by the unemployed Wiedemann.

When the speed at which a person cashes a cheque is open to criticism and supposedly a point of law, it isn't surprising then that Mathews also offers a critique that would have made the defendant's case far more air-tight: "It would have been better for the defendant to have left Darlington alone." Apparently Walpole's 'unnatural' inclinations, especially in that case, were simply a matter of stupidity, while Wiedemann's had been malicious. Mathews's opinion of the intellect of the jury must have been quite low, and he seemed to determined to frame these proceedings for them in such a way that the plaintiff 'couldn't get away with it.'

But here I am, spoiling it all for you. Read it for yourself. I don't mean to be making a case for or against either Wiedemann or Walpole, both of whom seem to have been involved in a dirty little affair that mushroomed out of control and had gone poorly in the long run for them both. What shocks me about this 'shocking' case, however, is actually the leading summary by Justice Mathews.

Oh—and I actually haven't spoiled the real surprise ending!

Read for yourself the surprising events of 19 June 1890, as recorded in the London Times:

(Before MR. JUSTICE MATHEWS and a Special Jury.)

WIEDEMANN v. WALPOLE. The trial of this action, which was brought to recover damages for breach of promise of marriage and libel, was resumed and concluded to-day. At the close of the proceedings yesterday the Solicitor-General had concluded his address to the jury on behalf of the defendant. The plaintiff then addressed the jury. The question of corroboration was a legal question with which she could not deal. If defendant thought her bad or wicked, why did be wish her to go to England with him? The people at the hotel could have found out everything if they had liked. When one looked at so many people who spoke well of her, it was impossible that she could have lived the life they said she did. The Count had not been called as a witness against her, although the defendant had plenty of means and could easily have called him. Her family had suffered very much by the conduct of the defendant. The defendant had not answered the Ietters of herself or her relations, who were in good positions. It had been said she delayed the trial. She did not delay the trial; she pressed the trial on. The letters she wrote showed she did not intend to extort money, but to claim the right of legal wife. In all her letters she wrote saying she had a right to be his wife, and the defendant never wrote and contradicted it. In the first trial she said her child was alive. She then thoroughly believed that it was alive. Her parents refused to correspond with her till she became the legal wife of the defendant. She had not corresponded with them since 1883. As to the petition of Count Cieuneville, it was a libel upon her. When she wrote to the Consulate they would not allow her to look at it. The defendant's evidence was altogether inconsistent. He said that when he gave her the cheque for £100 she was delighted, and almost in the same breath he said she told him she would make his life a burden to him. As to the ring, if she had stolen the ring, as suggested, the defendant could have properly claimed it, but he had never once written to her to claim it. He had asked Darlington to try to get it from her. The plaintiff then gave a full description of her movements from 1878 to 1882.

WIEDEMANN v. WALPOLE. The trial of this action, which was brought to recover damages for breach of promise of marriage and libel, was resumed and concluded to-day. At the close of the proceedings yesterday the Solicitor-General had concluded his address to the jury on behalf of the defendant. The plaintiff then addressed the jury. The question of corroboration was a legal question with which she could not deal. If defendant thought her bad or wicked, why did be wish her to go to England with him? The people at the hotel could have found out everything if they had liked. When one looked at so many people who spoke well of her, it was impossible that she could have lived the life they said she did. The Count had not been called as a witness against her, although the defendant had plenty of means and could easily have called him. Her family had suffered very much by the conduct of the defendant. The defendant had not answered the Ietters of herself or her relations, who were in good positions. It had been said she delayed the trial. She did not delay the trial; she pressed the trial on. The letters she wrote showed she did not intend to extort money, but to claim the right of legal wife. In all her letters she wrote saying she had a right to be his wife, and the defendant never wrote and contradicted it. In the first trial she said her child was alive. She then thoroughly believed that it was alive. Her parents refused to correspond with her till she became the legal wife of the defendant. She had not corresponded with them since 1883. As to the petition of Count Cieuneville, it was a libel upon her. When she wrote to the Consulate they would not allow her to look at it. The defendant's evidence was altogether inconsistent. He said that when he gave her the cheque for £100 she was delighted, and almost in the same breath he said she told him she would make his life a burden to him. As to the ring, if she had stolen the ring, as suggested, the defendant could have properly claimed it, but he had never once written to her to claim it. He had asked Darlington to try to get it from her. The plaintiff then gave a full description of her movements from 1878 to 1882.MR. JUSTICE MATHEWS summed up. He must say he thought the jury had heard the plaintiff's case with exemplary patience. He had had to interrupt her, not against her interest, but because if she had referred to documents not entirely evidence, a new trial could have been obtained, and the time of this trial would have been thrown away. He did not think that the jury, when they heard all, would have very much difficulty in dealing with the case. The action was for breach of promise of marriage, under which promise the plaintiff alleged she was seduced and became the mother of a child, of which the defendant was the father, and that then she was cast off. She told the story so simply that it was difficult to believe that it was not true. She represented herself as a modest woman. She was a talented and graceful woman. She said she was the victim of the violence of in Englishman; that, following it up, he induced her to live with him for three days. That was the story told by plaintiff, and that story she repeated to-day. The defendant asked them to take a very different view. He said it was a strange story, and there was not a scrap of evidence to support the promise of marriage. He said she was a woman who could not give a satisfactory account of herself. She was 32 at the time of the alleged seduction and defendant was 26. The Solicitor-General said the plaintiff inveigled the defendant in the first instance, and got a large sum of money out of him, and then persecuted him, his mother, and innocent wife. The Solicitor-General said they ought not to act on the statement of plaintiff or defendant without some corroboration; that in dealing with a woman like the plaintiff they should act with care and vigilance. Before he spoke of the facts, he must tell them about the law. A few years ago it was enacted that the plaintiff could give evidence in support of her action of breach of promise of marriage. Before, it was thought that it was unwise to depend on the evidence of the plaintiff. In 1870 it was thought the law might be relaxed, and it was thought that the plaintiff might be examined, only on condition that her evidence was corroborated in some material matter. The plaintiff's evidence would have to be discarded unless there was other evidence in support of plaintiff's statement. In this case all hung on one single thread. The plaintiff could not be heard, and plaintiff could not get a verdict unless they believed Cook. The plaintiff's advisers told her the difficulty of her position. She might have written letters, but the law imposed on no man the obligation of replying to them. The whole thing, therefore, turned on the evidence of Cook. Cook's recollection was precisely in point. If the evidence had been made for the occasion, it could not have been more exactly what was wanted. Cook said before he entered into a contract he had doubts as to the defendant's position with regard to the plaintiff. Cook said the defendant said to him, "I am not her husband, but I may have promised to marry her when I seduced her." The Solicitor-General asked them not to act on that evidence. Who was Cook? A retired policeman. Cook was compelled to admit he had to retire from the force for giving untrustworthy evidence. He had since been an inquiry agent. He made a claim on defendant which defendant refused to pay. The defendant had to pay money into Court which Cook took. Then this confidential agent handed the defendant's letters over to the plaintiff. The Solicitor-General said they helped the defendant as it showed the defendant, when he wrote them, told the same story then as he did now. It was clear that Cook, if not a liar, was a traitor. There was one point more against him. The plaintiff told the

m that Cook was a perjured villain: that he tried to take the ring by violence, and inflicted injuries on her. He denied that. If the statement by Cook was not true, there should be a verdict for the defendant. The Solicitor-General said the plaintiff's statement should not be accepted. Some of the plaintiff's statements as to her antecedents were tolerably clear. In 1869 she was 18. She had been educated as a governess, and earned her living as such during the early part of her career. In 1878 she said she came to England. The plaintiff gave the name of Pastor Wagner [pictured, right]. There was nothing that appeared in the case discreditable to him. He had taken up her case. He probably heard the story she told them now, without her then being under cross-examination. He saw her in 1883, and wrote to defendant, repeating statements made to him, and asked defendant to come to her assistance. He added she was starving. The plaintiff repudiated that indignantly. When the pastor wrote that letter, had he heard about the trip to Rome, and that she had stayed at a convent, and then went to Constantinople, where she did not know the names of the superiors? The pastor was not called. He wondered whether he knew all about that. The jury should bear in mind that no one who had spoken about the case knew so much about it as the jury, whether it was the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette or other editors who had been writing about it. After 1878 certain obscurity descended on the proceedings of the plaintiff. His Lordship then referred to the persons mentioned by the plaintiff. It was a singular thing that no single relative had been examined on her behalf. It appeared she had an uncle, an aunt, and two cousins at Innsbruck. A commission was sent out, and their evidence could be taken. Why was she left without the aid of a single relative? The plaintiff's answer was that they did not want their names mentioned in the case. If her relatives believed her story it was inconsistent with human nature that no relative should come forward to assist her. According to plaintiff's statement she went to her relatives. From 1880-1881 she went to other relatives in Pomerania. There was no explanation how a lady so accomplished as the plaintiff was should remain all that time doing nothing. Was the explanation that she was travelling with the young man she said she was engaged to? She then said she went to Rome with a countess. There were so many countesses mentioned he could not say which one it was, but he thought her name was Winsky. That lady was going to found a convent, and thought the plaintiff just the person to become a novice, forgetting her engagement to the young man. She said she was at the convent of Sacré Cœur from February to March. There was one person above all others in the convent, and that was the lady superior. The plaintiff could not tell the jury her name. She said she went back to Innsbruck, and then went to Vienna. And in February, 1882, the said the countess advised her to go to Constaninople. That was the account of those years which the plaintiff gave them. The Solicitor-General thought it a curious story that she should select, of all places in the world, Galata, to wait till the convent was ready for her reception in Rome. Did they think she was sent by Countess Winsky to wait at the convent at Galata till the countess's convent was ready? He must now turn to another part of the case. It appeared from a certificate that in 1880 there was another Valery Wiedemann in Berlin. The statements in that certificate were not evidence against the plaintiff. Their attention must be confined to the way the plaintiff answered the suggestion that she was the person mentioned in that certificate. She denied absolutely the suggestion that she was the mother of the child whose birth was recorded in that certificate. The Solicitor-General called their attention to the way in which she denied it. It appeared at one time as if she were going to admit it, but ultimately she denied it. There was another Valery Wiedemann, whose history was brought home nearer to the plaintiff than the first. It appeared that in December, 1881, there was a report of a complaint by Count

m that Cook was a perjured villain: that he tried to take the ring by violence, and inflicted injuries on her. He denied that. If the statement by Cook was not true, there should be a verdict for the defendant. The Solicitor-General said the plaintiff's statement should not be accepted. Some of the plaintiff's statements as to her antecedents were tolerably clear. In 1869 she was 18. She had been educated as a governess, and earned her living as such during the early part of her career. In 1878 she said she came to England. The plaintiff gave the name of Pastor Wagner [pictured, right]. There was nothing that appeared in the case discreditable to him. He had taken up her case. He probably heard the story she told them now, without her then being under cross-examination. He saw her in 1883, and wrote to defendant, repeating statements made to him, and asked defendant to come to her assistance. He added she was starving. The plaintiff repudiated that indignantly. When the pastor wrote that letter, had he heard about the trip to Rome, and that she had stayed at a convent, and then went to Constantinople, where she did not know the names of the superiors? The pastor was not called. He wondered whether he knew all about that. The jury should bear in mind that no one who had spoken about the case knew so much about it as the jury, whether it was the editor of the Pall Mall Gazette or other editors who had been writing about it. After 1878 certain obscurity descended on the proceedings of the plaintiff. His Lordship then referred to the persons mentioned by the plaintiff. It was a singular thing that no single relative had been examined on her behalf. It appeared she had an uncle, an aunt, and two cousins at Innsbruck. A commission was sent out, and their evidence could be taken. Why was she left without the aid of a single relative? The plaintiff's answer was that they did not want their names mentioned in the case. If her relatives believed her story it was inconsistent with human nature that no relative should come forward to assist her. According to plaintiff's statement she went to her relatives. From 1880-1881 she went to other relatives in Pomerania. There was no explanation how a lady so accomplished as the plaintiff was should remain all that time doing nothing. Was the explanation that she was travelling with the young man she said she was engaged to? She then said she went to Rome with a countess. There were so many countesses mentioned he could not say which one it was, but he thought her name was Winsky. That lady was going to found a convent, and thought the plaintiff just the person to become a novice, forgetting her engagement to the young man. She said she was at the convent of Sacré Cœur from February to March. There was one person above all others in the convent, and that was the lady superior. The plaintiff could not tell the jury her name. She said she went back to Innsbruck, and then went to Vienna. And in February, 1882, the said the countess advised her to go to Constaninople. That was the account of those years which the plaintiff gave them. The Solicitor-General thought it a curious story that she should select, of all places in the world, Galata, to wait till the convent was ready for her reception in Rome. Did they think she was sent by Countess Winsky to wait at the convent at Galata till the countess's convent was ready? He must now turn to another part of the case. It appeared from a certificate that in 1880 there was another Valery Wiedemann in Berlin. The statements in that certificate were not evidence against the plaintiff. Their attention must be confined to the way the plaintiff answered the suggestion that she was the person mentioned in that certificate. She denied absolutely the suggestion that she was the mother of the child whose birth was recorded in that certificate. The Solicitor-General called their attention to the way in which she denied it. It appeared at one time as if she were going to admit it, but ultimately she denied it. There was another Valery Wiedemann, whose history was brought home nearer to the plaintiff than the first. It appeared that in December, 1881, there was a report of a complaint by Count  Cieuneville that a woman, Valery Wiedemann, charged him with the paternity of her child, and also used threats towards him and that ultimately he had to call in the assistance of the consular office for protection. Oddly enough that woman's name was Valery Wiedemann. The plaintiff's account of that was that a person had picked up her passport and made use of the name. It appeared from the document that the Valery Wiedemann who was the subject of the proceedings had an introduction to the nuns at Galata [pictured, left]. So much for that part of the case. He would now go to the main incident. The plaintiff swore positively that she was not in difficulties as indicted by the statement in the document and that all the statements were trumped up, and that defendant, who was the evil genius in this case, had got these documents, which were concocted as to her journey to Constantinople. On the first trial she said nothing about her becoming a Catholic, and going to a convent. She then said she went on the invitation of German families. There was apparently no truth in that statement, as in this trial she told another story. Which of these stories was true? He need not go through the different weeks in September which ended in the plaintiff's employment by Logothetti. As to the evidence of Logothetti and Monoussos, he thought their evidence ought to be laid aside. It was clear that when the plaintiff was in the hotel, after the employment of the children was over, she had no means. One would have expected she would have gone back to her convent, but she remained in the hotel. The plaintiff was very likely to attract the defendant. The defendant said that he asked leave to go to her bedroom, was allowed, and remained there some time; that in the morning an occurrence took place, and the hotel proprietor sent her away; that the plaintiff told him what had happened, and that she wanted to go to Liverpool, and he sent her the money. That she left and stayed with him at the Luxembourg, and that no promise of marriage took place. Was his story likely or not? Now contrast it with the plaintiff's story. She said he kissed her and was repulsed, and was told of the young man in Germany; that she had been at the opera with the daughter of the house, that she retired to

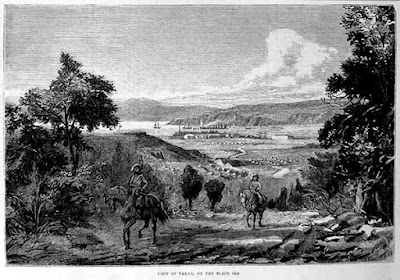

Cieuneville that a woman, Valery Wiedemann, charged him with the paternity of her child, and also used threats towards him and that ultimately he had to call in the assistance of the consular office for protection. Oddly enough that woman's name was Valery Wiedemann. The plaintiff's account of that was that a person had picked up her passport and made use of the name. It appeared from the document that the Valery Wiedemann who was the subject of the proceedings had an introduction to the nuns at Galata [pictured, left]. So much for that part of the case. He would now go to the main incident. The plaintiff swore positively that she was not in difficulties as indicted by the statement in the document and that all the statements were trumped up, and that defendant, who was the evil genius in this case, had got these documents, which were concocted as to her journey to Constantinople. On the first trial she said nothing about her becoming a Catholic, and going to a convent. She then said she went on the invitation of German families. There was apparently no truth in that statement, as in this trial she told another story. Which of these stories was true? He need not go through the different weeks in September which ended in the plaintiff's employment by Logothetti. As to the evidence of Logothetti and Monoussos, he thought their evidence ought to be laid aside. It was clear that when the plaintiff was in the hotel, after the employment of the children was over, she had no means. One would have expected she would have gone back to her convent, but she remained in the hotel. The plaintiff was very likely to attract the defendant. The defendant said that he asked leave to go to her bedroom, was allowed, and remained there some time; that in the morning an occurrence took place, and the hotel proprietor sent her away; that the plaintiff told him what had happened, and that she wanted to go to Liverpool, and he sent her the money. That she left and stayed with him at the Luxembourg, and that no promise of marriage took place. Was his story likely or not? Now contrast it with the plaintiff's story. She said he kissed her and was repulsed, and was told of the young man in Germany; that she had been at the opera with the daughter of the house, that she retired to  her room and that she noticed the key was gone; she now said that was a part of the conspiracy against her virtue; that she suddenly became aware of a man in the room; that he rushed upon her, overcame her, and committed a rape upon her; then she conveniently fainted. Next morning what happened? The plaintiff, upon whom this awful indignity had been perpetrated, went after the defendant to a neighbouring hotel. The defendant said that he determined to return by Varna [pictured, right, ca. 1877], so he drew a cheque for £100, and gave it her. The cheque was changed at once. The defendant then said that she threatened him for more money, but he got away. According to plaintiff's statement a promise or promises of marriage were made, after the possession of her had been obtained. Was that likely according to human nature? She also said he invited her to go to Cannes. Two months elapsed. She found her way to Cannes, and told the unhappy mother of the defendant that she had been overcome by the violence of the defendant. Was not that the last thing one would expect a modest woman to do? Mrs. Walpole said that plaintiff never said one word about a promise of marriage. At that time Valery Wiedemann wrote that letter of November 27, which he thought a most repulsive letter, suggesting she was pregnant with twins. The threat contained in that letter has been continued since. His Lordship read : —"I tell you this, since it is necessary for you to know it. I am indifferent to such things; I only regard my own self, and he who would dare to injure me, dishonour me, and put me to shame before all the world, would pay me for it with his life. I could not live in shame; I would sooner avenge myself, and I should seek after death." The mother telegraphed to her son. The defendant put himself in communication with Captain Darlington. It would have been better for the defendant to have left Darlington alone. The defendant perhaps thought he was in the hands of a woman who would stick at nothing. Was not that natural for a man who had read the letters she wrote him in November? Darlington went to her. The plaintiff had a signet-ring of defendant's. He instructed Darlington to get it. She said Darlington tried to get it by force. Darlington denied it. She said Darlington treated her with every indignity. Darlington had denied it. It was said against the defendant that the plaintiff had been treated very badly when Darlington left her on the railway journey. It was fair to defendant to say there appeared a telegram showing that defendant intended her to be taken to the Hotel Russie, and Darlington said she was left alone by mistake, and not intentionally. It was only fair to defendant to say that it was incredible that plaintiff could have a baby by him at that time. He believed her to be an adventuress, and acted accordingly. If plaintiff had been put to unnecessary pain by being asked about her confinement, who was to blame but plaintiff herself? On the former occasion she made a statement that the child was not dead. Did she mean to deceive the jury? It appeared now that the child was dead. The defendant's counsel said how could the jury act on the evidence of the plaintiff in this critical matter? Why did she say, the child was alive? In 1884 she wrote a letter saying that the child was alive. They would see that at the last trial, if she had said it died at the confinement, she would have been confronted with the letter, and therefore she refused to answer. Her explanation was that she knew nothing about it, as her family had discarded her, whereas in 1883 her mother brought an action for seduction. Every eight days, the plaintiff said, she wrote to defendant. If ever the sins of a man had found him out, that man was the defendant.

her room and that she noticed the key was gone; she now said that was a part of the conspiracy against her virtue; that she suddenly became aware of a man in the room; that he rushed upon her, overcame her, and committed a rape upon her; then she conveniently fainted. Next morning what happened? The plaintiff, upon whom this awful indignity had been perpetrated, went after the defendant to a neighbouring hotel. The defendant said that he determined to return by Varna [pictured, right, ca. 1877], so he drew a cheque for £100, and gave it her. The cheque was changed at once. The defendant then said that she threatened him for more money, but he got away. According to plaintiff's statement a promise or promises of marriage were made, after the possession of her had been obtained. Was that likely according to human nature? She also said he invited her to go to Cannes. Two months elapsed. She found her way to Cannes, and told the unhappy mother of the defendant that she had been overcome by the violence of the defendant. Was not that the last thing one would expect a modest woman to do? Mrs. Walpole said that plaintiff never said one word about a promise of marriage. At that time Valery Wiedemann wrote that letter of November 27, which he thought a most repulsive letter, suggesting she was pregnant with twins. The threat contained in that letter has been continued since. His Lordship read : —"I tell you this, since it is necessary for you to know it. I am indifferent to such things; I only regard my own self, and he who would dare to injure me, dishonour me, and put me to shame before all the world, would pay me for it with his life. I could not live in shame; I would sooner avenge myself, and I should seek after death." The mother telegraphed to her son. The defendant put himself in communication with Captain Darlington. It would have been better for the defendant to have left Darlington alone. The defendant perhaps thought he was in the hands of a woman who would stick at nothing. Was not that natural for a man who had read the letters she wrote him in November? Darlington went to her. The plaintiff had a signet-ring of defendant's. He instructed Darlington to get it. She said Darlington tried to get it by force. Darlington denied it. She said Darlington treated her with every indignity. Darlington had denied it. It was said against the defendant that the plaintiff had been treated very badly when Darlington left her on the railway journey. It was fair to defendant to say there appeared a telegram showing that defendant intended her to be taken to the Hotel Russie, and Darlington said she was left alone by mistake, and not intentionally. It was only fair to defendant to say that it was incredible that plaintiff could have a baby by him at that time. He believed her to be an adventuress, and acted accordingly. If plaintiff had been put to unnecessary pain by being asked about her confinement, who was to blame but plaintiff herself? On the former occasion she made a statement that the child was not dead. Did she mean to deceive the jury? It appeared now that the child was dead. The defendant's counsel said how could the jury act on the evidence of the plaintiff in this critical matter? Why did she say, the child was alive? In 1884 she wrote a letter saying that the child was alive. They would see that at the last trial, if she had said it died at the confinement, she would have been confronted with the letter, and therefore she refused to answer. Her explanation was that she knew nothing about it, as her family had discarded her, whereas in 1883 her mother brought an action for seduction. Every eight days, the plaintiff said, she wrote to defendant. If ever the sins of a man had found him out, that man was the defendant.  Why did she not bring her action at once? In 1888 the defendant became engaged to another lady, and this action was brought. They had to see what sort of a woman they were dealing with. What possible reason could there be for insulting that innocent lady? The Judge here handed to the jury the picture [left] of Miss Corbett [sic] written, over by the plaintiff. His Lordship next read one of the postcards written by the plaintiff to Mrs. Walpole, and continued, —The plaintiff walked about outside defendant's house. What greater persecution could there be than that? As to damages, they must deal with that. There was a charge of libel in the letters to Darlington. The jury had heard the letters read. If defendant wrote them in the honest belief that they were true, then plaintiff could not recover damages for that. The question for them was, did the jury believe there was a promise given by the defendant to plaintiff. If they did, then give her a verdict by all means.

Why did she not bring her action at once? In 1888 the defendant became engaged to another lady, and this action was brought. They had to see what sort of a woman they were dealing with. What possible reason could there be for insulting that innocent lady? The Judge here handed to the jury the picture [left] of Miss Corbett [sic] written, over by the plaintiff. His Lordship next read one of the postcards written by the plaintiff to Mrs. Walpole, and continued, —The plaintiff walked about outside defendant's house. What greater persecution could there be than that? As to damages, they must deal with that. There was a charge of libel in the letters to Darlington. The jury had heard the letters read. If defendant wrote them in the honest belief that they were true, then plaintiff could not recover damages for that. The question for them was, did the jury believe there was a promise given by the defendant to plaintiff. If they did, then give her a verdict by all means.The jury retired to consider their verdict at the adjournment for luncheon at 1 40. At 3 30 the jury sent word into Court that they could not agree upon a verdict.

The jury were sent for. The learned JUDGE, to the jury. —Have You discussed the case thoroughly, and is there no chance of an agreement ?

The Foreman. —No, my Lord.

The learned JUDGE. —It is so very important that you should come to an agreement. Is there no chance of your agreeing?

The Foreman. —The jury are so equally divided that there is no chance of their agreeing.

The jury were consequently discharged without giving a verdict. The plaintiff again conducted her own case. The Solicitor-General and Mr. William Graham were for the defendant.

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment