Yesterday I wondered aloud about the Rev. Barton R. V. Mills and his travels beginning in 1880 at Oxford, then moving to Rochester, to Battersea, to Broad Clyst, to St. George's Hanover Square, and to Sanremo [Or is it San Remo?] before becoming the instant vicar of Poughill after the Ligurian earthquake of 1887.

Upon further review, I've been doing some reading and I think I understand the process of Discernment and Training before Curacy in the process of "vicaration." However, that's as it is done today. Apparently today it takes 4 years as a curate before one can become a vicar.

If I understand it correctly, the first year is spent as a deacon, which permits one to take services, funerals, and baptisms. The second year is spent as a priest, and the responsibilities expand to the taking of Holy Communion and the marriage service. The third and fourth years are spent doing all of these. Let's assume, unless I disccover otherwise, it would have been the same during the Victorian era.

So, Barton Mills becomes a deacon in 1882, and subsequently a priest in 1883. He also earns his M.A. degree from Oxford that year, although I understand that was simply a matter of a fee, rather than further study or residence.

In 1884, Mills is at his curacy in Battersea, but by the end of the year, he's likely in Broad Clyst, having presented a paper in Exeter before New Year's 1885. It seems likely to me that Mills is spending as much time among the history tomes as he is among those strictly devoted to theology during this time, but it appears that hasn't been a problem.

In July 1886, he's been at famed St. George's long enough to have met his wife, Lady Catherine Hobart-Hampden, and married her, later departing for Samremo, where he mentions in many documents he was "chaplain", 1886-1887—but of which I can find no independent documentation.

In July 1886, he's been at famed St. George's long enough to have met his wife, Lady Catherine Hobart-Hampden, and married her, later departing for Samremo, where he mentions in many documents he was "chaplain", 1886-1887—but of which I can find no independent documentation.I don't doubt he was, though: He becomes vicar of Poughill the very day after that 1887 earthquake.

I guess what I wonder is why he moved around so much. Would it have been typical for a young cleric to have served his three years in three different curacies, constantly adapting to a new community, congregation, and rector? That seems like quite a bit of moving about, but perhaps it was required.

And maybe it's just the American in me, but it seems he had "friends in high places," with a father, Arthur Mills, who was a wealty, powerful M.P., relatives at Killerton on his mother's side, and being of the family of Lord Hillingdon, Sir Charles Mills, on his father's side. Over here, that would probably have "greased the skids" a bit—especially since a his father's friend and man he is named after, Rev. Charles John Vaughan, would have been at the time the Master of the Temple and Dean of Llandaff after accepting and quickly resigning the position of Bishop of Rochester. [I'll assume Vaughan was still successfully covering up his homosexuality and wielding some ecclesiastical clout.]

Of course, it was likely that it was, indeed, because of his connections that Mills was, indeed, placed into the last two curacies he served. Broad Clyst and St. George's would appear to have been plum positions that most young clerics would have longed for as they made their moves from place to place at the conclusion of each year during their four years of service. In addition, Broad Clyst would have allowed Mills to be near family for a year, something that seems to have mattered to him.

Subsequently, Sanremo would seem to have been a relatively plum job, too, located as it is on the Italian Riviera. But the Mills family unit seems to have been tight as far as Barton Mills goes. It is hard to imagine Barton joyfully and almost immediately taking his pregnant young bride off to Italy, away from their families at the budding of his young career and the beginning of his own new family. Was that really a move he would have wanted, and if not, had his connections no power to steer him away from it?

And it's hard to imagine that Barton's family connections and power had nothing to do with the fact that, the day after that Ash Wednesday morning earthquake in the Mediterranean, Mills was immediately installed as vicar of Poughill, near his family home in Budehaven, and that aging Rev. T. S. Carnew, thirty years the vicar of Poughill, was suddenly "promoted to the living of Constantine, near Falmouth," that very same day. That does make me wonder why he ended up there in the first place.

And it's hard to imagine that Barton's family connections and power had nothing to do with the fact that, the day after that Ash Wednesday morning earthquake in the Mediterranean, Mills was immediately installed as vicar of Poughill, near his family home in Budehaven, and that aging Rev. T. S. Carnew, thirty years the vicar of Poughill, was suddenly "promoted to the living of Constantine, near Falmouth," that very same day. That does make me wonder why he ended up there in the first place.I suppose another reason I wonder about Mills seemingly bouncing around as he served his curacies would be that he then continued to "bounce around" for the rest of his career, and that his son, George Mills—the real focus of my studies here—seems to have done the same for his entire life.

So: Did Barton Mills move from curacy to curacy simply because it was required, or did he tend to become restless? Or could there have even been something else?

He was obviously still very interested in his secular studies as an historian, evidenced by having done the writing, presentation, and publication of his research on Exeter's history of sieges during the autumn or early winter of 1884. Did this call into question his complete dedication to the church, was it lauded among the ecumenical, or simply a non-issue of a young cleric doing whatever he wanted in his spare time? I would imagine the TV and movie portrayal of the vicar having a round-the-clock job is somewhat exaggerated, so who knows how much there may have been around the parish in Devon to keep Mills busy full time?

I also can't help but recall that 1885 is the year of the publication of W. Gordon Gorman's book, Converts to Rome, which clearly cites Mills as having been a convert to Roman Catholicism even as he is moving from his curacy at Broad Clyst to one in Hanover Square.

Despite the fact that his conversion seems to most to be a non-issue, I can't help but surmise that this man who was deeply interested in the history of England and appears to have been a family man is suddenly assigned to the position of chaplain on the other side of the continent of Europe, in a location that is as beautiful as it is "out of the way."

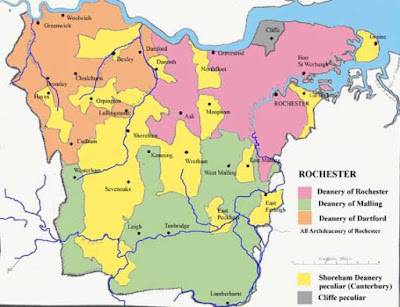

I can't help but think that Rochester's Diocesan Director of Ordinands—a fellow "who is paid to listen to you and God and work out whether it’s right that you are called to ordained ministry"—wouldn't have been approached by the Bishop about why it had been unexpectedly revealed in print that a Roman Catholic was about to begin serving an Anglican curacy at estimable St. George's Hanover Square. And I simply can't help but think that there might have been a few cross words spoken around the Diocese about the revelation. The more pieces of the puzzle I collect, the more it seems that one piece or another just doesn't seem to completely fit in with the rest, no matter how I arrange them.

That's why I suppose this whole time frame of 1880–1887 is so interesting to me. I'm sure in the end it'll all have been far more dull and ordinary than I'm imagining, and that everyone at the time was more laissez faire about the smaller goings-on in and around the Anglican church than I give them credit for. However, my "hole card" in the hand I'm relentlessly playing here is that Revd Galloway of the Savoy insists that 'what appears to be' regarding B. R. V. Mills simply can't have been: It all tallies up quite neatly if we all just assume a priori that Mills never could have been a Roman Catholic. I'll admit to still being very much undereducated about all of this, and I'd be interested in learning much more about this whole "vicaration" process and the prevailing politics of the Church of England as they existed in the late 19th century!

![Meredith and Co. [1933] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjlUeRNPnH8Xd8JT59QdtabQHRI6DI6Hqew57i6qixjOL3LjgUD9g22o3-wNlmBya36D5-6KZXX-sxLnktAfEqjlvTmdwyiIL2K6VHOGW2Wq9Pe8_oFGknENfVE1Xrkdj0b8FYXTz_6SMg/s1600-r/sm_meredith_1933.JPG)

![King Willow [1938] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgiz_iaQjinIbVw6yQ-W4hwx6wGJwMQH9azCs3Qacp9eX627B7Eq9hMn1wlHLzlkbcflHRWM8VcPX-1uteKbs4LA5q5Oq69WhrnhzBQLjpseK_M34PSoOOhTZ96EfVAGFehG53gZ0M4EvU/s1600-r/sm_1938.JPG)

![Minor and Major [1939] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgH5nj4Q6BNpzVEb1vyJeGV6ikuN4SFAyDa-jypIgbvdrxqcjHkNxqjrXH7ptZmge7oTTpn5QjAI0yCJPdI-fIzooCDD1TAA3RDxO9jzLcU3QOIhBWKiKNz6CPjCSTZgIPd9_4zM7LLpAw/s1600-r/sm_1939.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1950] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEgm_JPAXPpX0wb8bDkjYG67Sg1HePiPhRP6b9oUMWvkJhiW6XJzmxTQ7TBepfxpPgRrFNCRuumYRj-SAfU9Kw-uDsbO5HBtyxfQfClHVMJxJUkDpbkrCPhzpC4H_g_ctlirgnSla4vX1EQ/s1600-r/sm_1950.JPG)

![Meredith and Co. [1957?] by George Mills](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEg0zRm3-CCmA8r2RrBmrACDvmxJjoBjfxUoPI9yc6NWu1BZ3dd89ZvCixmmKZe1ma0QiDIrsDZNqf-8h1egh0JLiRYHagXAqQ1UknWPy6SksK76psYPcEMLGa_Aj7wo2vMFPo0aMdcx_pg/s1600-r/sm_meredith.JPG)

No comments:

Post a Comment