Mail's in!

I've received parcels from England and Australia in the last couple of days, but they haven't quite lived up to the excitement of the arrival of the 1933 edition of Meredith and Co. last week.

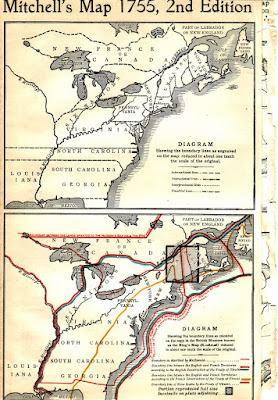

A real disappointment came from Australia, whence I received a a partial copy of Col. Dudley A. Mills's significant publication, British Diplomacy in Canada: The Ashburton Treaty. It was published, not as a stand-alone piece of literature, but in United Empire: The Royal Colonial Institute Journal, New Series 2 (Oct 1911) on pages 681-712, and included the apparently definitive 'Mitchell Maps' [above, left].

Unfortunately, I've received only pages 681-702.

Dudley Mills is the uncle of George Mills, and spent his career traveling the world with the Corps of Royal Engineers. A brief biographical sketch on-line describes him in this way [my emphasis]:

"Dudley Acland Mills was born at Eastbourne in 1859. He appears on the 1861 census staying at Killerton House at Broadclist in Devon, the home of his grandfather Sir Thomas Dyke Acland. His parents were Agnes Lucy (née Acland) and Arthur Mills, the M.P. for Taunton from 1857 to 1865 and the M.P. for Exeter from 1873 to 1880.

Dudley Acland Mills joined the Royal Engineers as a Lieutenant in 1878, rising to the rank of Captain in 1889 and Major in 1897. In 1896 he married Ethel Joly de Lotbinière. They had one son and two daughters. Colonel Dudley Acland Mills died on 22 February 1938. According to his obituary in The Times (26 February 1938), he was 'an authority on things Chinese and early maps and a man of all-round culture and knowledge.'"

Researching the Ashburton Treaty is on my big "to do" list of all things Mills, but the journal United Empire itself describes Mills's well-researched document full of painstakingly reconstructed maps as "a valuable step towards clearing away misapprehensions which, in the past, have sometimes clouded the relations between Canadians and their Mother-land."

I'd like to think I could report on the entire article, but may only be able to survey through page 702, depending on the reply I receive from Serendipity Books in West Leederville WA, Australia, about the missing pages.

I also received printed material from Alton, Hants in the U.K.: A brand-new, apparently self- or privately-published edition of An Account of Stewardship: 1979-1984 by Major General Giles Hallam Mills, Resident Governor and Keeper of the Jewel House, Her Majesty's Tower of London [title page, right]. It has been implied that General Mills [not to be confused with the American cereal company] is a relative of George Mills and family, but I've been unable to verify that independently.

It's a thin, 41-page text, hand bound by E. A. Weeks and Son, London, and is comprised of nicely reproduced photocopies of typewritten pages, probably "pica" if I'm correctly recalling the days before word processors when a "font" was better known as a reservoir than as a typeface. It promises to be a very factual read.

How Hallam Mills is related to the Mills family of our interest isn't quite known, but I'll read the volume anyway. At least it arrived with all of the 41 pages intact.

Meanwhile, wish me luck in my quest to receive the missing pages 703 to 712!

It's a gorgeous, sunny, hot morning here in Florida, and I'm still basking in the glow of pitcher Roy Halladay's perfect  game for my beloved Philadelphia Phillies last night in Miami [left]. It was only the 20th perfect game in the history of baseball, and the second this year. The last time there were two perfectos in a season was 1880, accomplished by pitchers from the Providence Grays and the Worcester Red Rubys—the first two perfect games ever thrown.

game for my beloved Philadelphia Phillies last night in Miami [left]. It was only the 20th perfect game in the history of baseball, and the second this year. The last time there were two perfectos in a season was 1880, accomplished by pitchers from the Providence Grays and the Worcester Red Rubys—the first two perfect games ever thrown.

I'm not sure exactly how a perfect game might translate to cricket, but I have read exciting passages in the books of George Mills about bowlers striving for "hat tricks." My cricket knowledge is obviously not exactly what it should be.

I recently read about the triple-centuries in Test cricket, accomplished by only 20 different players since 1930. Would this be a similarly rare accomplishment?

• The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) (commonly known as "the Brighton line" or "the Brighton Railway") was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1922. [...] Haywards Heath was in use by 1858.

• The London, Brighton and South Coast Railway (LB&SCR) (commonly known as "the Brighton line" or "the Brighton Railway") was a railway company in the United Kingdom from 1846 to 1922. [...] Haywards Heath was in use by 1858.